In 1984, India was making semiconductors before Taiwan’s chip giant TSMC even existed. Today, TSMC controls 54% of the global market while India’s semiconductor ambitions can be found gathering dust in government files that have been “moving” for half a century.

It’s a classic case of snatching defeat from the jaws of victory – with a literal fire providing the plot twist that would make even Bollywood scriptwriters blush.

But Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s declaration from the Red Fort that “by the end of this very year, a Made in India chip, built in India by the people of India, will arrive in the market” suggests India is finally ready to stop treating semiconductors like a bureaucratic hot potato. His 79th Independence Day announcement represents more than political rhetoric – it’s the culmination of efforts to revive an industry that once showed tremendous promise but got spectacularly derailed by tragedy and the usual suspects of Indian bureaucracy.

“Files related to semiconductors started moving 50–60 years ago… but the idea was stalled, delayed, and blocked,” Modi acknowledged with characteristic understatement, noting that “the very idea of semiconductors was aborted before it could take shape.” In other words, India managed to turn a head start into a half-century head-scratch.

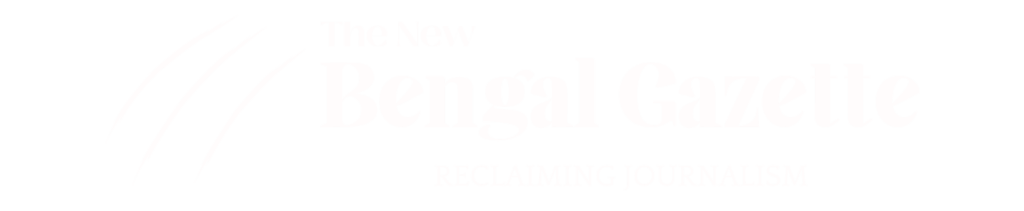

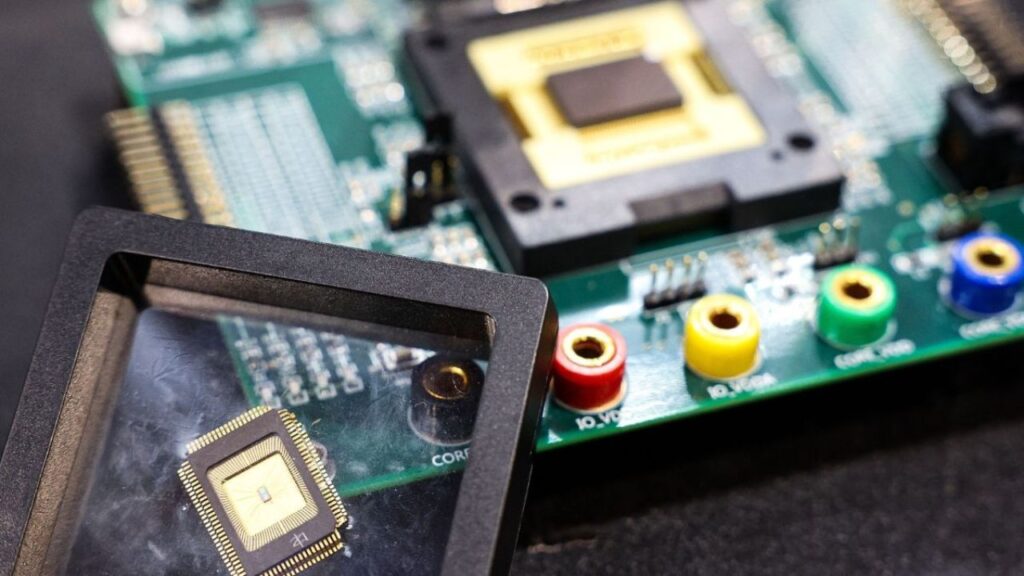

The story of India’s semiconductor ambitions begins with remarkable promise and ends in mysterious tragedy. The Semi-Conductor Laboratory (SCL) in Mohali started manufacturing in 1984, three years before Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) – today’s global chip leader – was established. This early start positioned India as a potential pioneer in the semiconductor industry.

However, in 1989, a mysterious fire destroyed SCL’s facilities at the 51-acre campus in Punjab. Whether the incident was accidental or sabotage remains unknown, but its impact was devastating. The fire effectively halted India’s semiconductor progress, taking nearly a decade for operations to resume in 1997. By then, the global landscape had transformed dramatically, with countries like Taiwan and South Korea establishing dominance in chip manufacturing.

The contrast is stark: while TSMC now makes 54% of the world’s semiconductor chips and clocked $60 billion in revenue in 2022, SCL struggles with just $5 million in annual revenue. “Had it not been for a mysterious fire that destroyed the SCL facility at Mohali in 1989, India would have become a global leader in semiconductors,” industry observers note.

Today, SCL continues operating from its Mohali facility, primarily serving strategic sectors including space, defense, railways, and telecommunications with 180-nanometer chips. While these legacy nodes remain relevant for critical applications requiring reliability over cutting-edge performance, SCL’s current capacity of 700 wafers per month reflects decades of underinvestment.

The facility has achieved notable successes, including fabricating the Vikram Processor (1601 PE01) for the Chandrayaan-3 mission and producing charge-coupled devices for the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO). However, its capacity utilization hit an abysmal 10% due to lack of marketing efforts, non-existent customer support, and limited government attention over the years.

Kamaljeet Singh, director general at SCL, maintains that “no other fab in the world can boast of so many technologies at one place,” highlighting the facility’s unique position in supporting academia and startups with accessibility for both research and limited volume production.

Recognizing the strategic importance of semiconductors as “the brains” behind modern technological developments from routers to weapons, India launched the Indian Semiconductor Manufacturing Mission in 2021 with a $10 billion outlay. The initiative offers comprehensive support, including fiscal support of up to 50% of project costs for semiconductor fabrication units (a manufacturing plant that produces semiconductor chips or components, such as Silicon Carbide (SiC) and display driver chips).

The government’s policy framework under the Make in India program includes multiple incentive schemes: Production Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes offering 4%-6% incentives on incremental sales for electronics manufacturing and up to 5% for IT hardware, Design Linked Incentive (DLI) scheme providing 50% support on eligible R&D expenditure, and the Chips to Startup (C2S) program aimed at training 85,000 engineers in Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI) and embedded systems.

These efforts are beginning to yield results. The Union Cabinet recently approved four semiconductor projects worth ₹4,594 crore under the India Semiconductor Mission, bringing the total number of approved chip manufacturing facilities to 10 across six states, with projected investments of approximately ₹1.6 lakh crore.

The semiconductor ecosystem is witnessing unprecedented private sector investment. Micron Technology kicked off in 2023 with a ₹220 billion testing and packaging plant in Sanand, while Tata Electronics, in collaboration with PSMC, announced a massive ₹910 billion fabrication facility in Dholera, Gujarat, focusing on 28-nanometer power management chips.

Other significant investments include CG Power’s joint venture with Japan’s Renesas investing ₹76 billion in a Sanand semiconductor plant, and Kaynes Semicos establishing a ₹40 billion facility capable of producing 6 million chips daily. The ₹3,706 crore joint venture between HCL and Foxconn was recently approved to set up the country’s sixth semiconductor facility in Uttar Pradesh, focusing on display driver chips with production slated for 2027.

India’s fabless semiconductor ecosystem is thriving, driven by innovative companies like AGNIT, Incore, and Mindgrove. These companies are leveraging India’s significant talent advantage, with Indian engineers accounting for approximately 20% of the world’s semiconductor design workforce as per InvestingIndia.gov.

AGNIT focuses on RF components for telecom and power electronics, while Incore leads in processor design for automotive and edge AI applications. Mindgrove develops power-efficient chips for consumer electronics and defense products. With government support and initiatives like the Semiconductor Mission, India’s semiconductor industry is poised for growth, enabling the country to become a major player in the global semiconductor market. Innovation is flourishing.

Despite the domestic push, India faces a significant trade gap in semiconductors. The country imported approximately 18 billion and 15 billion chipsets in 2022 and 2023 respectively, valued at ₹1.1 lakh crore and ₹1.3 lakh crore, while exports remained at just $516 million in 2022, primarily to the United States, Hong Kong, and South Africa.

This trade imbalance underscores the challenge ahead. Currently, India imports 90% of its semiconductor requirements, with China, Singapore, and Vietnam being key suppliers. However, the global “China plus one” approach, as noted by Financial Services firm UBS, presents opportunities for India to capture supply chain diversification.

The government has allocated approximately ₹10,000 crore for SCL’s modernization, aiming to upgrade from current 180-nanometer technology to 28-nanometer capabilities. Communications and IT Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw emphasized the government’s vision: “We want SCL to support startups and industry for R&D and prototyping, as well as increase its capacity and strength for chip exports.”

The modernization plan includes increasing capacity to 24,000 wafers per month and establishing 12-inch wafer fabrication capabilities. “We are looking for companies which will install the fab, run it, and then hand it over to us,” says Sudhir Thakur, group head at SCL’s Project Planning Group.

Despite the momentum, India’s semiconductor ambitions face significant challenges. Building a semiconductor fab costs upwards of $10 billion and takes years to become profitable. The country confronts a talent gap of 250,000-300,000 skilled professionals by 2027 according to TeamLease reports, while lacking a robust ecosystem of raw material suppliers and high-precision chipmaking tools.

Gender imbalance presents another challenge, with women accounting for only 25% of India’s 220,000-strong semiconductor workforce. In leadership roles, the disparity is starker, with men holding 93%-95% of top positions.

Recent setbacks include the withdrawal of Adani Group and Zoho Corp from their semiconductor projects, citing concerns about weak domestic demand and difficulties securing technology partners internationally. The 2023 collapse of the Vedanta-Foxconn joint venture further highlighted partnership challenges.

Taiwan and South Korea dominate 80% of global chip manufacturing, making it difficult for India to compete in high-end manufacturing. Advanced chip-making remains dependent on ASML’s EUV lithography machines, a monopoly held by the Netherlands.

India is addressing these challenges through strategic diplomacy, participating in the Quad’s semiconductor supply chain initiative with the US, Japan, and Australia. Agreements with Japan and the EU for R&D collaboration, and discussions about the first US-India defense semiconductor unit in Uttar Pradesh, demonstrate India’s commitment to international cooperation.

According to experts cited by the Observer Research Foundation and Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, India needs a Taiwan-style strategy combining policy, talent, innovation, and institution building. A proposed India Semiconductor Research Centre (ISRC), similar to Taiwan’s ITRI, could drive this vision forward.

With the global chip market expected to reach $1 trillion by 2030, India aims for a 10% share. John Neuffer, President and CEO of the US-based Semiconductor Industry Association, highlighted the acceleration of supply chain diversification, indicating significant opportunities for India to expand its role in this critical industry.

The semiconductor sector’s expected growth of approximately 26% CAGR over 2022-2032 to touch $270 billion creates a substantial opportunity window. As Modi announced, “six different semiconductor units are coming up on the ground” with “four new units already given the green signal,” signaling India’s determination to transform from a semiconductor importer to a manufacturing powerhouse.

From the ashes of Mohali’s mysterious fire to the promise of cutting-edge fabs across multiple states, India’s semiconductor renaissance represents a nation’s resolve to reclaim its position in the technology that powers the modern world. The success of this revival will determine whether India can finally realize the semiconductor dreams that were once reduced to ashes.