Photography by Luca Gaetano Pira

Published on 21 August 2025

On June 9th, the Catholic Church in Spain issued an unprecedented public apology to the women who were imprisoned in one of the most repressive—and least known—institutions of the Franco regime: the Patronato de Protección a la Mujer, Spain’s equivalent of the Magdalene Laundries. After decades of silence, few surviving women have now decided to speak out. These women were detained between 1941 and 1985 for reasons that today seem unimaginable: being poor, pregnant out of wedlock, rebellious, politically active, lesbian—or simply considered “morally suspicious.” These institutions, run by religious orders under the patronage of Carmen Polo, Franco’s wife, operated under the guise of social assistance but were in fact centers of punishment and re-education, where isolation, forced labor, and psychological violence were routine. Many of the survivors are still alive, and their testimonies are moving, urgent, and deeply relevant.

Madrid, June 9, 2025

The word “forgiveness,” spoken by representatives of the Spanish Conference of Religious (CONFER), echoed through a hall filled with women who had spent their youth locked in institutions run by the Patronato de Protección a la Mujer. Immediately, the restrained emotion turned into a wave of indignation. They stood up and firmly shouted: “Truth, justice, reparation. No forgetting, no forgiveness.” What was meant to be an act of historical reconciliation ended up revealing what is still missing: the full truth about one of the most morally repressive structures of the Franco regime.

Corridor and Room in the Patronato

In the centers managed by the Patronato de Protección a la Mujer, daily life followed a strict and regulated routine. The day began with mass, usually on an empty stomach, followed by long periods of prayer. Obedience and discipline marked the rhythm of the day, leaving no space for personal expression. Much of the day was spent working in sewing workshops, laundries, or kitchens. The inmates performed these tasks without pay, as part of a regime that justified forced labor as a method of correction and moral redemption.

Minors from the Patronato of Seville

Communication was severely restricted: talking among inmates was prohibited, correspondence was censored, and there was no access to phone calls or permission to leave. The rules were numerous and often unstated, but any infraction could result in immediate punishment. Common sanctions included isolation, confinement in punishment cells, or public humiliation. Ideological and moral control was in the hands of the religious congregations in charge of the centers, which enforced a rigid interpretation of Catholic morality. The feeling of confinement and repetition marked the experience of many inmates, who described time as static, without horizon or clear references to the outside world.

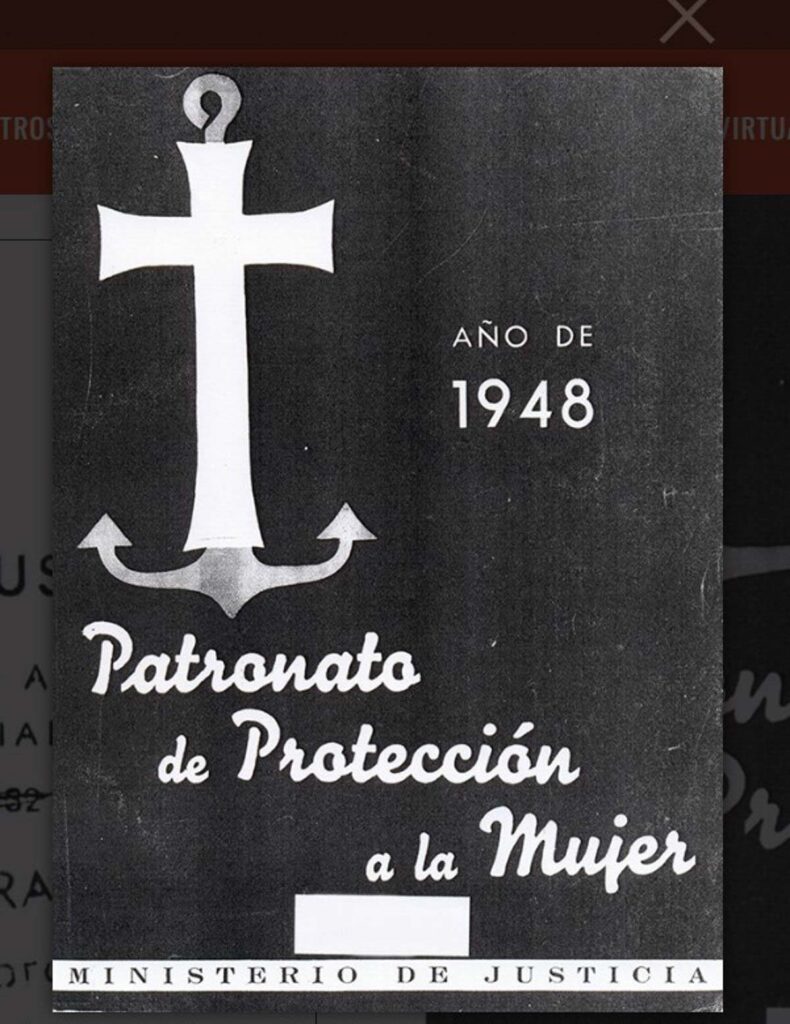

Sign of the Patronato during the Franco regime

One of the first practices upon entering a Patronato center was a gynecological exam. It was routinely carried out without explicit consent, with the purpose of determining whether the girl was “complete”—in other words, whether she had engaged in sexual activity. The information obtained—medically unnecessary—shaped the moral classification of each young woman and determined how she would be treated inside the institution. This invasive and humiliating practice reflected the absolute control exercised over the bodies and privacy of the inmates.

Paca Blanco

Paca Blanco was only 15 when she was institutionalized. That night, she returned home after a neighborhood party. Waiting for her were her mother, aunts, and other relatives. Without explanation, they put her in a car and took her directly to the Villalba reform school in the mountains near Madrid. It wasn’t a spontaneous decision. Later, Paca learned that her family had previously visited the center. They saw her as a rebellious, difficult girl.

Paca Blanco

Her deeply Catholic and conservative environment feared she would follow in her late father’s footsteps—he had been a communist and unionist. They wanted to “correct” her before it was “too late,” in their words. Paca never accepted the confinement. She escaped twice from the Villalba center and did the same in every institution she was moved to. During one of these escapes, she became pregnant. As a result, she was sent to Peña Grande, the reform school reserved for mothers. There, she lived with a persistent fear: that her child would be taken from her.

Mariaje López

Mariaje López was eight years old when she was placed in the orphanage at the Palace of Eugenia de Montijo in Madrid, managed by the Oblates of the Most Holy Redeemer. The decision was made by her mother after her father died. Living with her violent maternal grandmother had become unbearable, and her mother thought the orphanage would be safer. Mariaje stayed there for five years.

Mariaje López

Her testimony, collected in the book Por caridad, describes a life of constant surveillance and a strict routine. The girls worked from an early age: knitting, scrubbing floors, cooking, and washing clothes. Although she was not in a Patronato center, her experience was not unlike that—many girls were transferred to Patronato institutions at age 15, continuing their confinement under another name. “Girls who repeatedly wet the bed were physically punished by being rubbed with stinging nettles on their vulva and anus.”

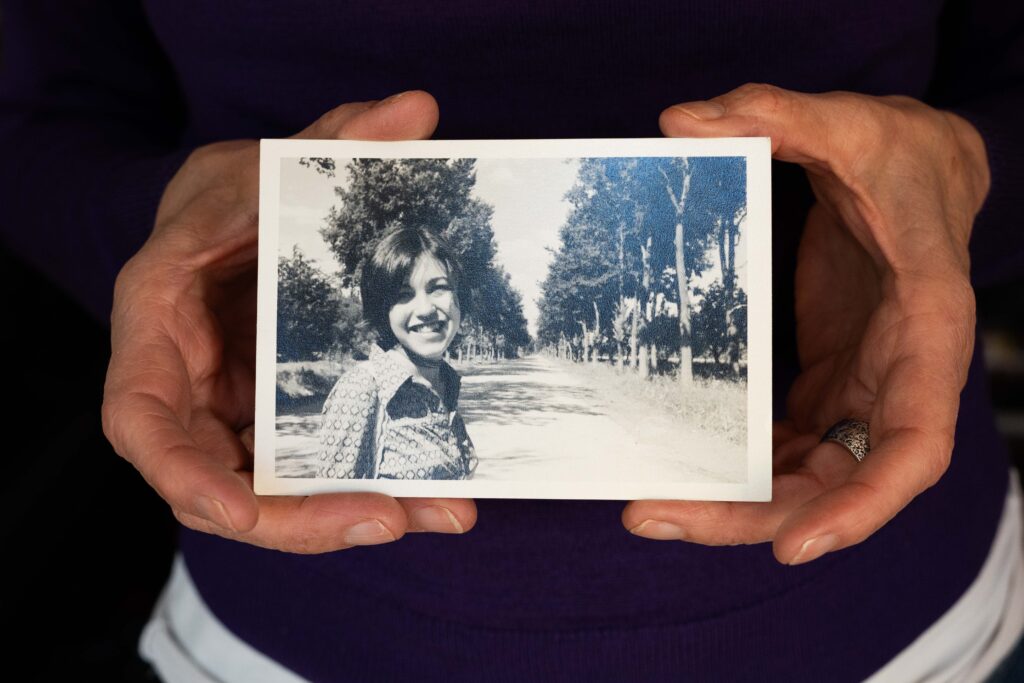

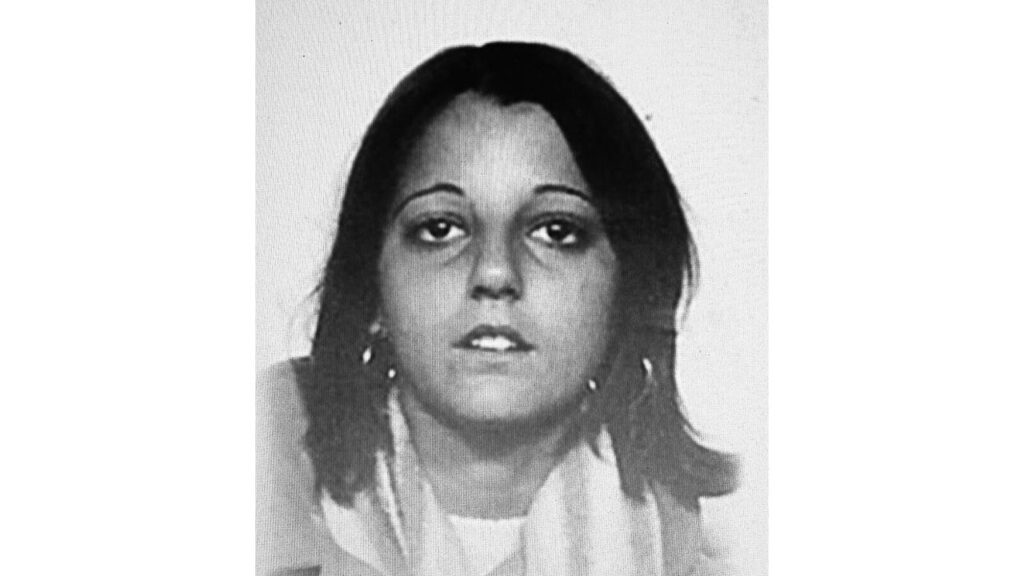

Mariona Roca Tort

Mariona Roca Tort was 17 when she was institutionalized in 1969 for her anti-Franco activism and for running away from home. For three years, she passed through various religious and psychiatric centers, where she was subjected to treatments designed to break her will. At the Adoratrices center in Madrid, she was forced to work unpaid in sewing workshops.

Mariona Roca Tort

While they stitched coats, religious texts were read aloud to prevent conversation among the girls. After attempting to escape and later returning voluntarily to protect her friends, she was isolated. As a form of resistance, Mariona stopped eating, which led to her transfer to the San Miguel psychiatric clinic in Madrid. There, she was subjected to electroshock therapy and insulin shock treatments that induced comas. During her internment, she was visited by psychiatrist Vallejo-Nájera, who tied her to the bed and told her she would not be released until she gained weight.

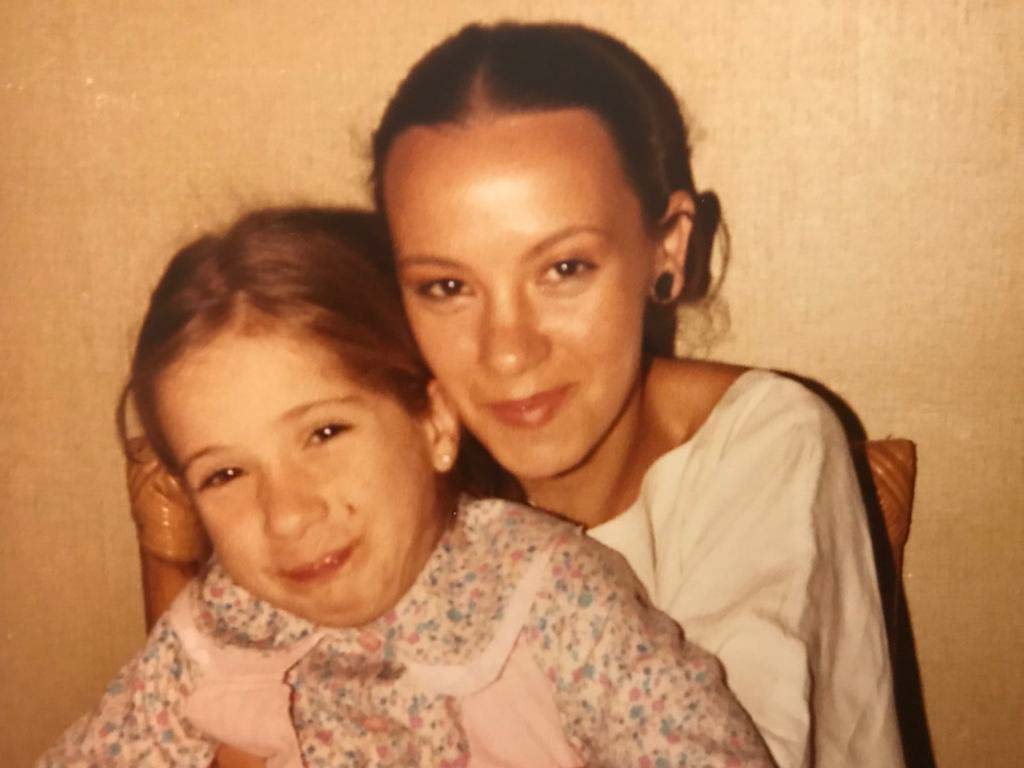

Churra

Between 1983 and 1985, Churra was institutionalized for being pregnant and unmarried. She was just over twenty and living in Spain, already in democracy, where the Movida Madrileña filled the streets with freedom and art. But inside the Patronato, the rules hadn’t changed.

Churra

Her pregnancy was treated as a moral offense. Churra was isolated, subjected to rigid schedules, and denied any say over her body or her motherhood. What terrified her most was that her daughter might get sick. In those cases, babies were taken to the infirmary and sometimes never returned. Mothers were told the child had died, with no proof, no body, no goodbye. Later, many discovered these children had been handed over—or sold—to regime-friendly families.

Consuelo García del Cid

At 16, Consuelo García del Cid was drugged by her family and woke up in a reform school run by the Adoratrices nuns on Calle Padre Damián in Madrid. She had no idea how she got there. Her participation in anti-Franco demonstrations had alarmed her wealthy, conservative family, who decided to “correct” her. A year later, she escaped. She was sent to the Bon Pastor reform school in Barcelona.

Consuelo García del Cid

When she got out, she promised her fellow inmates she would write about everything. She fulfilled that promise 36 years later with Las desterradas hijas de Eva. Since then, she has never stopped researching and giving voice to the victims of the Patronato. Inside the centers, most inmates were minors forced to work under the guise of “training.” They received no wages, had no contracts, and no legal recognition as workers. Some religious congregations ran workshops that functioned as hidden industries, producing goods for third-party clients—some even for large retailers like El Corte Inglés.

María Victoria González

María Victoria González (“Viki”) was born in the Basque Country in 1958. Her mother, after giving birth to her fifth child, killed the newborn and buried him in secret. A neighbor discovered it and reported her. The mother was imprisoned. With their mother in jail and the family broken apart, the authorities separated the children. María Victoria and her sister were sent to a Patronato center in Madrid.

María Victoria González

Their younger brothers were sent to a Salesian school in the Basque Country. While at the Patronato, María Victoria was repeatedly raped by her father during permitted visits. The nuns allowed it. Her sister, after leaving the center, turned to prostitution and later died of AIDS. Like so many others, the promise of “protection” became institutionalized violence.

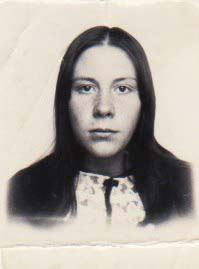

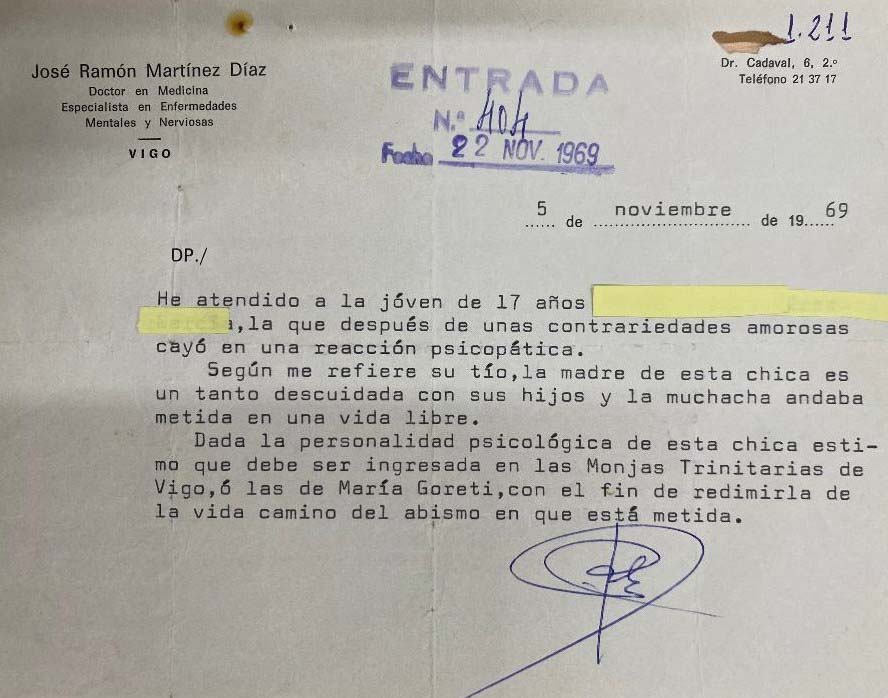

Intake record of a woman at the Patronato

At the June 9 event, many of these women were present. They expected acknowledgment, but found censorship: the audio recordings omitted references to sexual abuse, stolen babies, and extreme violence. No religious order admitted its role in the network of forced adoptions. The survivors made it clear: “They only apologise for what they’re willing to acknowledge.” Today, these women demand real justice: access to archives, legal recognition, financial reparations, and the inclusion of their testimonies in Spain’s official narrative of democratic memory. Because history cannot be written without them. And without truth, there can be no forgiveness.

Luca Gaetano Pira is an Italian documentary photographer and audiovisual artivist based in Barcelona. His work centers on recovering the historical memory of marginalised communities, particularly through portraits of survivors of institutional violence and the use of archival materials. In recent years, he has developed projects on the repression of LGBTQ+ individuals under the Southern Cone and Iberian dictatorships.