Photography by Quamar Equbal

Published on 4 February 2025

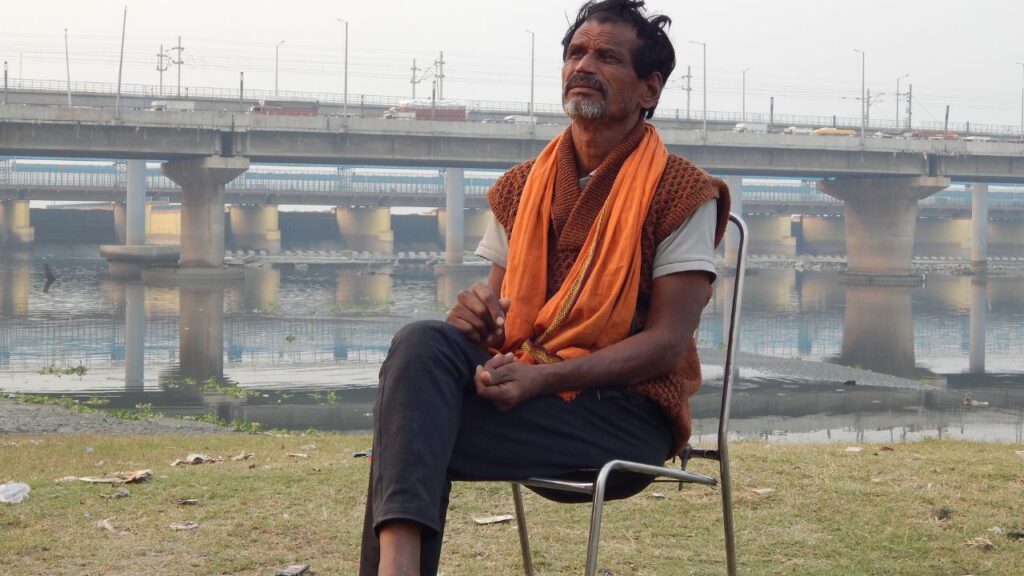

Kalindi Kunj, a prominent area along the Yamuna, is considered one of the most polluted regions. Despite its toxic waters, the Yamuna remains a lifeline for many. Farmers irrigate their crops, cattle graze along its banks, and boatmen rely on it for sustenance. Scavengers, corpse retrievers, and devotees continue their activities, while believers gather to pray, reflecting the deep cultural, religious, and economic dependence on the river. BJP organised a protest in Karnal, Haryana, opposing recent remarks made by Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) chief Arvind Kejriwal and Delhi Chief Minister Atishi regarding pollution in the Yamuna River. The protest saw BJP supporters raising slogans against the AAP leaders and also burned effigies of Arvind Kejriwal.

The Yamuna River, revered as a sacred lifeline of Delhi, has once again become a stark symbol of environmental neglect, with thick layers of toxic white foam blanketing its surface at key stretches like Kalindi Kunj and Okhla Barrage. This alarming phenomenon, reported widely in recent weeks, has reignited public outcry and drawn sharp criticism from environmentalists, health experts, and residents who fear the river’s worsening state poses severe risks to both human health and the ecosystem. As the foam—an annual occurrence during winter months—continues to spread, it underscores the persistent failure to address the root causes of the Yamuna’s pollution, despite decades of government promises and billions spent on cleanup efforts.

The Yamuna, originating from the Yamunotri Glacier in the Himalayas, stretches over 1,376 kilometers through Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Delhi, and Uttar Pradesh before merging with the Ganga in Prayagraj. Historically, it has been a cornerstone of India’s cultural, spiritual, and economic fabric, sustaining ancient cities and nourishing agricultural lands. In Delhi, the river’s 22-kilometer stretch supports nearly 60% of the city’s drinking water needs and holds deep religious significance, with festivals like Chhath Puja drawing thousands to its banks. Yet, this revered river has been reduced to what a recent parliamentary panel called a “virtually non-existent” entity in the capital, choked by untreated sewage, industrial effluents, and solid waste.

The toxic foam, caused by high levels of phosphates, surfactants, and other pollutants, is a visible manifestation of the river’s dire condition. According to the Delhi Pollution Control Committee (DPCC), the Yamuna’s Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD)—a measure of organic pollution—soars from 4 mg/l at Palla, where it enters Delhi, to a staggering 66 mg/l at ITO Bridge, far exceeding the 3 mg/l threshold for a clean river. Dissolved oxygen (DO) levels, critical for aquatic life, are nearly zero in the Delhi stretch, rendering the river “dead” and incapable of supporting fish or other organisms. The foam forms when soap-like surfactant molecules, primarily from untreated sewage and industrial waste, mix with the river’s turbulent flow, trapping air and creating frothy bubbles that can persist for days.

This year’s foam has been particularly severe, with drone visuals capturing thick, snow-like layers floating across the river’s surface at Kalindi Kunj, a site significant for religious rituals. During the 2024 Chhath Puja, devotees waded into the foam-covered waters despite warnings from health experts about the risks of skin irritation, respiratory issues, and infections from exposure to harmful chemicals and pathogens like E. coli. The Delhi High Court, citing these risks, banned Chhath Puja rituals on the river’s banks in November 2024, a decision that sparked protests but underscored the gravity of the crisis.

The sources of the Yamuna’s pollution are well-documented but stubbornly unresolved. Delhi’s 17 major drains, with the Najafgarh drain being the primary culprit, discharge approximately 1,900 million liters of untreated sewage daily into the river. Industrial units, both authorized and unauthorized, contribute heavy metals, dyes, and chemicals, while agricultural runoff from upstream states adds phosphates and pesticides. The parliamentary standing committee on water resources noted in March 2025 that even if all sewage treatment plants (STPs) in Delhi operated at full capacity, the river would remain polluted due to the lack of freshwater flow downstream of Wazirabad. This scarcity, exacerbated by upstream damming and water extraction, leaves the Yamuna too weak to dilute its toxic load.

Efforts to address the foam specifically have been temporary and inadequate. In October 2024, the Delhi Jal Board (DJB) sprayed 13 tonnes of silicone dioxide-based anti-foaming agents at Okhla Barrage to reduce frothing ahead of Chhath Puja. While this provided short-term relief, DJB officials admitted it was a stopgap measure and advocated for permanent sprinkler systems to administer anti-surfactant solutions more efficiently. Critics, including former National Green Tribunal chairperson Justice Swatanter Kumar, have slammed such approaches as superficial, arguing that “spraying chemicals to hide the foam is like putting a bandage on a broken leg.” Kumar, who led the 2015 Maili se Nirmal Yamuna Revitalisation Project, emphasized the need for ecological solutions, such as wetland restoration and stricter regulation of industrial discharges, over cosmetic fixes like motorboats or concretized riverfronts.

The Yamuna’s plight has long been a political flashpoint in Delhi. During the 2025 Delhi Assembly elections, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) capitalized on public frustration, promising a three-year plan to revive the river. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, invoking the river as “Yamuna Maiya,” pledged to make it pollution-free, and the Jal Shakti Ministry drafted a “Yamuna Master Plan” inspired by Gujarat’s Sabarmati riverfront project. The plan focuses on waste removal, drain cleaning, and stricter STP monitoring, but skepticism remains. Between 2015 and 2021, over ₹6,856 crore was spent on Yamuna cleanup initiatives, yet the river’s condition has barely improved. The Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), which governed Delhi until early 2025, faced accusations of mismanagement, with former Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal’s claim that Haryana was “poisoning” the river debunked by data showing Delhi’s drains as the primary polluters.

Beyond Delhi, the Yamuna’s pollution affects millions downstream. In Uttar Pradesh, cities like Agra and Mathura rely on the river for irrigation and drinking water, but its toxic load threatens crops and public health. The river’s ecological collapse has also decimated fish populations, impacted fishing communities, and disrupted migratory bird habitats along its floodplains. Environmentalists warn that the Yamuna’s decline could have cascading effects on the Ganga, given their confluence, undermining the ambitious Namami Gange Programme aimed at cleaning India’s holiest river.

Proposed solutions, like The Energy and Resources Institute’s (TERI) 10-point action plan, offer hope but face bureaucratic hurdles. TERI’s recommendations include revising the 1994 water-sharing treaty to ensure minimum environmental flow, banning direct discharges from dhobi ghats, and monitoring non-point pollutants like ammonia. However, experts like those at Deccan Herald argue that cleaning the Yamuna in three years is unrealistic unless pollution sources are addressed at their origin, rather than focusing on downstream treatment. Community-led initiatives, such as local cleanups and awareness campaigns, are gaining traction, but their impact remains limited without systemic change.

As the Yamuna continues to froth with toxic foam, it stands as a grim reminder of Delhi’s environmental crisis. The river, once a cradle of civilization, now reflects the consequences of unchecked urbanization, industrial growth, and political inertia. For Delhi’s 20 million residents, the fight to save the Yamuna is not just about restoring a river but reclaiming a vital part of their heritage and health. Without urgent, coordinated action, the toxic foam will remain a haunting symbol of a river—and a city—in distress.